Thomas Brooks 1776-1851

“Reader remark thy time is Short,

How Short thou canst not tell.”

Thomas’ autograph and his words from

the family bible.

Born: December 24, 1776, possibly Melbourne, Derby, England, but also

possibly Shoreditch, London, England.

Died: November 24, 1851, probably near Troy or Champlain, New York.

Spouse: Ann West married Saint Leonards, Shoreditch,

London, England on January 26, 1814.

Children: Thomas

Wallace Brooks

Kezia Brooks (see below)

Occupation: Cabinetmaker

Father’s name: Dr. David

Brooks, probably from Stratford, Connecticut

Mother’s name: Possibly Ann Luffman

from Oborne, Dorset, England

Siblings: Unknown

Half-Siblings: David Brooks

Henry

Sands Brooks

Anna Brooks

1

other sister

A Note About Thomas Brooks

Mother

Ann Luffman

and Dr. David Brooks may never have been married. Oborne History Center transcriptions of Oborne Township, Dorset, England records indicate that the

Banns of Marriage were announced August 20, 1776, but that no civil license was

issued. However, no license was ever

issued. My theory is that Dr. David

Brooks around or after December 1776, trying to escape warrants for his arrest

from the American Continental Congress, fled from New York back to

England. While there, he met Ann Luffman and she became pregnant about March of 1776. The groom’s pre-existing

marriage that was neither dissolved nor annulled which would be grounds to

prevent the marriage. Still being

married to Hannah and also being Catholic, I propose that Dr. Brooks now

“escaped” back to New York. In studying Oborne records, the David Brooks that married Ann Luffman was not from the area, nor did he die there. The couple did not settle there, nor is there

any record of any births for them or for her individually. Ann Luffman is the

youngest daughter of John and Ann Luffman, born

January 5, 1755. Her siblings are:

William Luffman (b. May 30, 1748), Donsabell Glover Luffman (b.

September 3, 1750), and John Luffman (b. February 10,

1752 and d. November 19, 1960).

Thomas and Ann Brooks Prior to Immigration

Thomas and Ann were married

in London and both of their children were born in London, England. If Thomas was born in the more northern

Derbyshire region, he must have moved to London sometime before 1814. I am then curious about the ten year gap

between their marriage and the birth of the first child. On a hunch, I explored court proceedings for

both areas, however came up empty. I do

not find any record of him being jailed.

However, I did find a possible brother for Thomas, a Joseph Brooks who

was a farmer in Derbyshire. He appears

to have had a difficult time of it and was eventually caught poaching in

1812. Joseph was fined, but did not

serve any time in jail. Now here is some

pure speculation… Thomas may have been living and working on the family farm in

Derbyshire. Then following the troubles

of his brother in 1812, parted company and moved to London. There he met and then married Ann in

1814. (And here is another stretch…)

Over the next possibly ten years he may have learned his trade of becoming a

cabinetmaker. The next time his name

comes up in any records is as a witness in a forgery trial on April 9,

1829. Thomas identifies himself as a

housekeeper that lets two rooms at No.4, Bulls Head. Google Earth helped spot that address for me

and it is within walking distance of St. Leonard’s Church. I can easily imagine Thomas Brooks,

diligently working at his trade, with his wife and two children and renting out

two rooms at his place trying to make ends meet. Three years later, with the economy failing

and epidemics approaching, they pick up and go to North America.

There are two cases outlined

in The Proceedings of the Old Bailey

that mention a Thomas Brooks of Shoreditch who identifies himself as a merchant

or a cheese monger. The first takes

place on Guy Fawkes Day (November 5, 1828) with the trial taking place December

4, 1828. Thomas was robbed and beaten by

an unruly mob. The other trial again has

Thomas as a victim of theft when his shop was robbed on January 3, 1831. The trial took place on February 16,

1831. Again, I’m not

fully understanding how Thomas is a cabinetmaker when he emigrates. However, a number of the Derbyshire Brooks do

identify themselves as grocers or victualizers from

which becoming a cheese monger could then be an easy progression.

Daughter Kezia was born

October 3, 1826. She married Robert H.

Rencor on November 26, 1842. They had

two sons: Charles K. Rencor, born November 4, 1843 and Edward T. Rencor, born

September 25, 1845. (There is an Oliver

W. Rencor from New York State, born 1825 that could be a brother to

Robert. Oliver married and moved to

Oregon.)

The Emigration of Thomas Brooks and

Family:

A Summary of What I Have Learned and Some

Speculations

Introduction

“Thomas

Brooks came in to this Goddamn Country 8 of June, 1832 in the time of Cholera

from London, England with a wife and two children, Thomas and Kezia.” That is how Thomas put it, in his own words,

as he entered his notes into the family Bible.

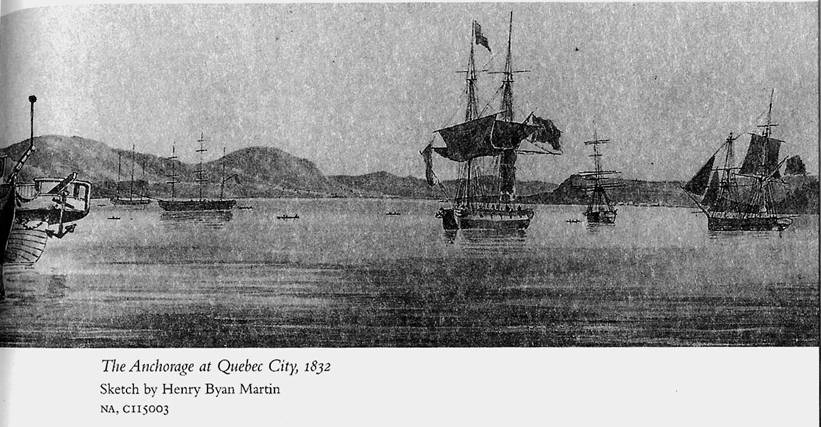

They arrived at Quebec, Canada, most likely at the Gross Île Quarantine

station. Later, they continued to this

country (USA) in Champlain, New York, naturalizing in 1842 or 1843. You may read about this journey and learn

other details in Ida’s letter. Ida was Thomas’ granddaughter and was

interested in genealogy. I am fortunate

that she had direct contact with her emigrant grandparents and I have copies of

her family history notes. She did share

them with other relatives and there are different versions, some details vary,

but the essential facts and dates are consistent in each. (Ida is the daughter of Myron Walker Brooks and he is the son of Thomas Wallace Brooks, son of our Thomas Brooks.)

Thomas

Brooks and his bride Ann West were married at Saint Leonards, Shoreditch,

London, England. This is not a

well-to-do part of town. Many of

London’s workhouses, almshouses, and various infirmaries and jails were located

in Shoreditch. The Brooks family

originally came from Derby, England (from Men

of Progress, more in “Brooks Brothers Connection” below). LDS records show that the West family was

from Timsbury, England. Why or how these

two individuals came to be in London is not known, but they did meet and were

married there on January 26, 1814.

An 18th

century print of

St. Leonard, Shoreditch as seen on Wikipedia.

Why and How They Emigrated

The

detail that the family was originally going to Canada struck me as

curious. Why Canada? How and when did they turn and go to the

United States? The wealthy often chose

New York as a point of arrival for the greater comfort and speed of the

American ships. Of course there were

plenty of poor folk arriving at Ellis Island, too, but Canadian arrivals at

their quarantine station, Gross Île, located in the Saint Lawrence River near

Quebec, appear to be poor folk exclusively.

The

Brooks, like other families in 1832, were escaping from a deeply troubled

England. The country was facing rapid

population growth, especially among the working poor, accompanied by a

diminishing availability of food, resources and jobs. The population was also fleeing from the

impending threat of disease, especially cholera, which had reached London early

in 1832. The poorer communities were

especially vulnerable due to inadequate sanitation and questionable water

supplies. Clues from Ida and various

other resources that discuss British emigrants have led me to the conclusion

that the Brooks family was likely one amongst many of Britain’s poor. Cabinetmaker Thomas Brooks may have been

following the promise, “In new communities, anyone at all familiar with

carpentry must have been sure of work…it was much easier to start a business…”

in British North America (aka Canada) than to eke out a meager existence in

England. (Quotes and details regarding

the Petworth Project are from the book Assisting Emigration to Upper

Canada, The Petworth Project 1832 - 1837, by Wendy Cameron and Mary

McDougall Maude, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston,

London, Ithaca, 2000.)

In

London, near rioting occurred during the late 1820’s when food and work started

to become scarce. These were known as

the Swing Disturbances. Parliament saw

the need to do something about the growing numbers of poor people and passed a

number of laws, also, various Lords and churches created schemes to assist

people to emigrate to Canada, the United States, Australia, and other

locations. How many made the passage to

Quebec? The total arrivals from all

points in Quebec for 1832 is noted as 51,746 (from various sources, including Canada

and the Canadians, Volume I, by Sir Richard Henry Bonnycastle, eBook published

by Project Gutenberg, 2006). This amount

is more than double of what any previous year’s totals were.

Seal or stamp used by the Petworth

Emigration Committee.

Found on the Petworth Emigration

Project website.

One

of these emigration plans was lead by Reverend Sockett and financed by Lord

Engremont of Petworth and became known as the Petworth Project of 1832 to

1837. This was an effort for assisting

emigration to Upper Canada for England’s growing numbers of impoverished

families. (Upper Canada means up the St.

Lawrence River from Lower Canada. Upper

Canada is now known as the Province of Ontario and Lower Canada is the Province

of Quebec.) There were 3 ships that were

part of this project in 1832 and only one of them arrived in Quebec in June,

that being the Brig England on the 15th

with 164 emigrants. The Brig England’s next stop was in York

(Toronto) on July 1. The approximately

two week journey appears to have been typical when a stop was made at the

quarantine station at Gross Île.

However,

June 8th is cited as the date of arrival. This date does coincide with the arrival of

another Petworth ship, the Lord Melville,

with 603 emigrants, which arrived in Quebec days earlier on May 28 and then

continued to Montreal, arriving there on June 8. The third Petworth Project ship in 1832 was

the Eveline, which reached Quebec on

May 28 with an unknown number of emigrants.

The Eveline may have illegally

bypassed stopping at Gross Île because it quickly continued to Montreal,

arriving three days later on May 31, it then made a third stop at York (Later

known as Toronto.) on June 8. So here

are three possible ships the Brooks may have traveled on. An interesting side note is that the Brig England had a close call with disaster

off the

The

surname Brooks does appear in the Petworth

Project’s collective ships passenger lists, though the book does not

specify which ship an emigrant may have been on, nor does it elaborate on the

size or make-up of the families.

However, there is an Eliza Brooks that is specifically mentioned because

she married a man named Penfold, possibly William Penfold, who was a

superintendent aboard the Lord Melville. Eliza was from Thakeham,

The Petworth ships departed

from England’s southern port of Portsmouth; the Eveline and Lord Melville

on April 11 and later the Brig England

on May 8. The vast majority of these

emigrants came from various parishes in the county of West Sussex, but the

authors note that 25 emigrants came down from London. The book emphasizes that “the cholera

epidemic got in the way of counting.”

The first confirmed cases of Cholera identified in Quebec were on June

6, 1832. (However, this detail is not

well supported, as noted in the paragraphs below regarding the Cholera

epidemic.) Ida recounts that, “…they

were taken ashore at night and he [Cabinetmaker Thomas Brooks] was put making

coffins. Grandpa [Son, Thomas Wallace

Brooks] used to tell his family his first memory of things was to stand his

turn holding a candle so Great Grandpa could build more coffins night and

day.” It is most likely that the Brooks

were held at Gross Île while the rest of the emigrating passengers continued on

to their planned Canadian communities.

This suggests how the Brooks, now separated from their group, may have

changed their direction and went on to New York State, USA.

Picture from the book Assisting Emigration to Upper Canada, The

Petworth Project 1832 - 1837,

by Wendy Cameron and Mary McDougall Maude,

McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston, London, Ithaca, 2000.

Recall that Thomas’ wife,

Ann (West) Brooks, hails from Timsbury, England. Timsbury is located slightly north and west

of the departure point of Portsmouth, which places it within the heart of the

area where the majority of the Petworth emigrants were coming from. Further, the family name West, Ann’s maiden

name, does appear amongst the list of surnames.

Specifically noted are Elizabeth West, who married John White in England

shortly before leaving, and Sarah Clowser (nee West), who similarly married an

Edmund Sharp, Sr. I have too little

information regarding the West family to make any further conclusions and Ida,

our family historian, makes no mention about the Brooks having travelled with

other relatives or in-laws. I think it

is plausible Ann’s family helped make connections for her, Thomas and family to

come south from London and partake in the project.

Cholera

epidemic of 1832

Many

of the records of this period are incomplete due to the overwhelming

distraction of the cholera epidemic and the Petworth Project book’s authors

had to recreate lists from other sources such as letters from emigrants back to

England. In the case of our Brooks

family, Thomas’ father had left England earlier. Presuming that mom was also not a part of his

life, there would be little reason for Thomas to write a letter back to

Ida’s reporting of Thomas

Wallace Brooks first hand descriptions of building coffins with his father

makes me want to know more about how the cholera quarantine was handled by

Quebec. As a ship arrived, it first had

to visit the Gross

Île Quarantine Station, established by legislation published March 26, 1832

from a petition started by the Medical Board in Quebec City in 1831. “The station was hastily established in 1832

as a defense against cholera, was staffed by the British army.” “Quarantine officers were as anxious to keep

the healthy moving as to hold the sick.”

Hospitalization was mandatory at Gross Île for all cases of five

communicable diseases: cholera, smallpox, scarlet fever, measles, and

[generically any] fever. A suspect ship

would be held and forced to fly a yellow flag.

Keeping a healthy family like the Brooks at the station to help with

burial of the dead appears to be unusual and certainly exposed them to all

illness. It’s a miracle they survived

and were able to continue their journey.

(Quotes and details regarding the Petworth Project are from the book Assisting

Emigration to Upper Canada, The Petworth Project 1832 - 1837, by Wendy

Cameron and Mary McDougall Maude, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal

& Kingston, London, Ithaca, 2000.)

A research article posted

on Ancestry.com adds this description of quarantine operations at Gross Île,

“Ships with ill passengers were required to stop at Gross Île and unload their

passengers, then be thoroughly cleaned before any passengers were allowed back

on board. The deceased were removed and

buried on the island. The ill were

placed in hospital and the remainder of the passengers were

required to live in tents on the island for a minimum of forty days. At the end of forty days, the healthy were

placed on the first ship that had room and allowed passage to Quebec

City.” The same article adds, “When the

quarantine station was planned and first opened, it was assumed that room for

1,000 people (200 in hospital, 800 in quarantine) would be more than

enough. But within the first year of

operation it was discovered that Gross Île was ill-equipped to handle all new

immigrants.”

In the paper The

1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio, by G.

William Beardslee, the spread of cholera throughout the world is

described. “In the West the disease traveled the familiar trade

routes into Afghanistan and into Russia by 1827. By 1831 cholera had infected all of Russia's

major cities despite quarantines and sanitation measures. These defenses were

ineffective primarily because cholera victims invariably infected nearby water

supplies, including creeks, streams, and ultimately the major rivers. Russian

troops carried the disease into Poland in the winter of 1831. By June of that

year, it had arrived in Hungary, Austria, and Germany. By April of 1832, cholera reached

Paris.” “Cholera invaded the British

Isles at Newcastle in October of 1831…by April of 1832, it had spread north

into Scotland and across the Irish Sea into Ireland.” A digest of one of

London’s newspapers, Bell’s Weekly

Messenger, for the Year 1831 notes for November 2nd, “A royal

proclamation is issued relative to riots at Derby, Nottingham, and Bristol, and

a reward of 1,000l offered for the apprehension of any rioters.” The pattern of rioting following cholera outbreaks

is common.

The general belief is that cholera first arrived in

Canada with the Brig Carricks on June

8, 1832. This date might even suggest

that our Brooks family may have travelled on that fateful ship. However, the Carricks arrived in Montreal on June 8, not Quebec. On

June 3 (1832) Captain James Hudson brought his Brig Carricks to anchor at Grosse Île after a harrowing voyage from Dublin in which 42 of this 133 passengers

had died from “some unknown disease”.

Despite the danger signs, the survivors were given a clean bill of

health and allowed to proceed. On June 7

the survivors of the Carricks,

reached Quebec City and those who did not go on to Montreal dispersed to their

lodgings in the city. The next day, a

man died in a waterfront boarding house, and two others died within twenty four

hours. “Only then”, recalled a doctor “did the truth flash on our minds”. The

disease the authorities had worked so hard to contain had broken out of

quarantine. (The

Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America, edited by Arthur

Gribben, publ. by University f Massachusetts Press, Boston, MA, 1999.) No mention is made of a family being left

behind at the quarantine station, which would have been the Brooks. Ida’s

letter clearly points out that the Brooks stayed behind. The absence of such a detail from the

accounts of the Brig Carricks tends

to make me believe that it is doubtful that the Brooks travelled via the Carricks.

In 1875, the United

States House of Representatives in their report regarding the cholera epidemic

of 1873, when reviewing the past epidemic of 1832, cited that “prior to

June 3rd [arrival of the Carricks]

there had arrived 4 vessels [at the Gross Île Quarantine Station on the Saint

Lawrence] carrying at least three hundred and seventy emigrants, among whom

fifty nine cholera deaths had occurred.”

Canada’s

website regarding Gross Île states that in 1832 only 39 travelers were hospitalized on

Grosse Île, and 28 were buried.

Meanwhile, cholera claimed 1,900 victims in Montréal, and twice that

number in Québec. Essentially the

quarantine station was a failure.

Infected people had been allowed to leave the island and, in spite of

military authority and canons aimed at them, many ships bypassed the station,

continuing on to Quebec and other ports.

My sense is that it is most likely that the Brooks

family arrived in one of the 3 Petworth Project ships, possibly the Lord Melville, but it will be extremely

difficult to document conclusively. It

is possible that they arrived aboard the infamous Carricks. Another ship that

I have no information about, but was arriving in this same time period is the

Brig Cletus. The Canadian government did not require

ship’s arrivals and their passenger lists be documented until 1865. We may never know the actual number of ships

or their identities. Hopefully more

passenger lists or other documentation will be found.

I have contacted the

management at Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site of

Canada in hopes of visiting the site and doing some research. They have been helpful and I thank the staff

sincerely. However, when I asked about

records regarding the management, staffing, housing, or employees in that first

year at Grosse Île, I received this unfortunate statement from Jo-Anick Proulx, Manager. “We do not have any records left of the early

years of the quarantine station. All the

information regarding the period between 1832 until 1877 was burned during a

fire in the year 1878 on Grosse-Île. The

files were kept in one the twelve lazarettos.

Sadly, the building was completely destroyed with all the files

concerning the management of the station.”

The epidemic was at its height during the summer

months of 1832. The date of when it was

considered to be over varies amongst sources, the earliest being September 9

and the latest as Christmas in December.

Somewhere within this time frame is when the Brooks family moved on to

the state of New York. Thomas Brooks

states in the family Bible, “Thomas Brooks is my Name, England was my nation,

Champlain is my Deviling Place, Christ my Salvation When I am dead and in my

Grave and all My Bones are Rotten.” They

most likely continued up the Saint Lawrence River to Montreal, turned south

into New York State, USA and into Lake Champlain, settling in Champlain, NY, a

small town just west of the lake. Later,

family members moved south to Lansingburgh and Troy, New York, both being

somewhat north of Albany.

The first installations

of the station quarantine on the Grosse Île, in 1832

© Parks

(I

find it interesting that at the right side of the group of people on the beach

in the center there appears to be

a

seated boy, a man, a woman, and then a girl wearing red.

What

are the odds that those are the Brooks?)

Above:

View of the Officers’ Barracks, Grosse Isle, St. Lawrence River, September,

1832.

Pencil

on wove paper drawing by Ralph Alderson.

Part

of an exhibition called By The Soldiers of the Crown: Military Views, Maps, and Plans

of Lower Canada.

Below: Photo (ca. 1900) by D. A. McLaughlin of the Grosse Île Quarantine Station.

Both images from the Library and Archives

Canada.

Brooks Brothers Connection

Who

was Thomas Brooks’ father? We learn from

Ida’s letter that this man was in the state of New York, most likely in New

York City. Ida says, “When the epidemic

was over they came on down to Troy, New York.

He [Thomas

Brooks]

had lost track of his brothers. (No mail

those days.) But in later years Grandpa [Thomas Wallace Brooks] found them in New

York. And found them the prosperous Brooks Brothers Clothing.”

Ida’s letter mentions Thomas seeking

out his Brooks brothers and finding that they had a clothing business in New

York, New York.

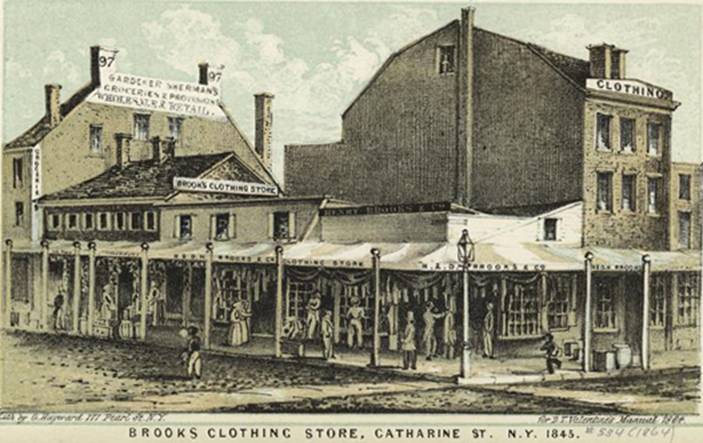

Sketch found on Photobucket

website as part of an article about Knickerbocker Village history and the

July 16, 1863 Draft Riot.

The Brooks Brothers’ “Golden Fleece”

logo.

I have no less than three versions of Ida’s “Brooks

Family History” and two copies of Ida’s letter. None of them are exactly the same, but the

salient points have been consistent. In

one of the “Brooks Family History” booklets, I believe it is the earliest and

most complete one, she elaborates, “There were several of great grandfather’s

half-brothers and their families who had come to this country some years

earlier, but they never were traced.”

So let’s explore that Brooks Brothers connection and Dr. David Brooks a little more.

The Men of

Progress book (See sources above.) is a Who’s Who type of book written in

1898, focusing on business leaders from Connecticut. In its discussion of John Brooks, the then leader

of the Brooks Bros Clothing business, Men

of Progress describes John Brooks’ family history as, “His ancestors came

originally from Derby, England. He is

the great-grandson of Benjamin Brooks, and grandson of Dr. David Brooks,

physician of Stratford, Connecticut.”

Solid connections for Dr. David Brooks have been elusive. He is not buried at the family plot within

Sands Point Cemetery in Nassau County, New York, with his wife, Hannah, and two

of his children, Henry Sands and Anna Brooks.

I’m hoping that one of the above ‘mentions’ might produce more leads.

Thomas’ half-brother Henry Sands Brooks very likely

travelled to England on business. Henry

Sands Brooks’ Day Charge book is partially illustrated in Brooks

Brothers Centenary; 1818 – 1918 and a number of the monetary entries

carry the typical 3-column format for British monies. It is apparent from Aunt Ida that Thomas knew

of, and had met, his half brother prior to 1832. That meeting had to have occurred in England,

most likely London. (I am aware that

much of Colonial America and Canada used the British Pound as their currency,

so the simple presence of this currency in his bookkeeping is not of itself

conclusive for Henry Sands Brooks having actually travelled to England.)

I have not found a suitable Benjamin or David Brooks

in the various vital records available online for Stratford, Fairfield County,

CT. This could indicate that they had

not yet arrived from England or had already moved on towards New York. Men of

Progress states clearly that Dr. David Brooks died in New York City in

1795, so the latter may be possible.

I’ve tried to locate vital records for Derby, England

and only found marriages. More specifically,

records for the Parish or County of Derby, aka Derbyshire. There I did find Benjamin Brooks marrying

Mary Beresford on March 26, 1733, both being of the Parish from the town of

Melbourne. (Melbourne is about 120 US

miles north-northeast of London, and Edinburgh is about another 300 US miles

further north.) This information matches

that of an LDS contributor who then estimated that Benjamin Brooks would have

been born about 1710.

Studying these marriage records further suggests

possible siblings to Benjamin may be: Hugh Brooks, Robert Brooks, and a Mary

Brooks that married a Nathan Hazard.

Possible additional children for Benjamin and Mary

who may have stayed within the Parish may be: Benjamin, Mary, William, Frances,

and Ann.

Earlier Derbyshire marriages that suggest who

Benjamin’s parents may be are: John Brookes married to Mary Garot on July 4,

1700, or Joseph Brookes married to Hannah Cheeswell on May 7, 1711. The date on the latter leads me to prefer it

as a best guess.

Of course this is all speculation and assumes that

the same family stayed within the same Parish.

Do any of these names appear in Stratford, CT vitals therefore

suggesting an emigration? In a word,

no.

In

Conclusion?

It

is apparent from the Family Bible and other sources that Thomas Brooks did not

want to willingly share with us the identity of his mother or father. From what writings I have from Thomas, he

could be described as religiously minded and bitter. Understandable, since life forced him to face

many tremendous hardships. If he was

indeed a half-brother of the more famous Brooks family of clothing fame, it

appears that it was because their father had an affair or other marriage while

studying abroad.

Thank you,

Jim Kowald

Back to the Genealogy Main

Page